Diaspora Legal

Diaspora Legal

Equity, Prosperity and Dispute Resolution Across Borders

Are China's "Traditional Fishing" Rights Really so fishy?

Mar 28, 2016

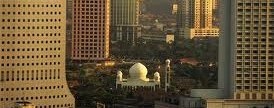

An International Incident

As reported in the Jakarta Post, two Chinese vessels, namely fishing vessel MV Kway Fey and a coast guard vessel, were involved in an incident with an Indonesian patrol boat at around 2:15 p.m. local time on Saturday, 19th March 2016. According to that report, the incident began when the Indonesian patrol captured the MV Kway Fey in Natuna waters. The Chinese vessel was allegedly fishing illegally in Indonesia’s Exclusive Economic Zone.The KP Hiu 11 patrol boat approached the fishing vessel and apprehended eight of its crew. The patrol officers were about to escort the MV Kway Fey from the scene when a Chinese coast guard boat approached and hit the fishing vessel. It was suspected that this was an attempt to prevent Indonesian authorities from confiscating the Chinese fishing vessel. To avoid a conflict, the Indonesian patrol boat officers left the Kway Fey and returned to the KP Hiu 11 command with the eight arrested crewmembers from the fishing vessel.

In a verbal communication conveyed by the chargé d'affaires of the Chinese Embassy in Jakarta, China said the incident occurred in China’s traditional fishing zone. Indonesia has rejected that explanation and made a formal demarche on China.

In the protest note, Indonesia conveyed three points of objection to measures taken by the Chinese maritime security patrol, which Jakarta believes protected illegal fishing activities in Indonesian waters. In the first point, the Indonesian government protested the Chinese maritime security vessels, which contravened Indonesia’s sovereignty and jurisdiction over its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and continental shelf areas. Second, Indonesia protested violations over law enforcement measures by Chinese authorities in the EEZ and continental shelf areas. Third, the Indonesian government protested violations committed by the Chinese maritime security boats against the sovereignty of Indonesia’s maritime territories.

An incident with implications

Unlike the 2013-2014 incursions into Indonesian territorial waters by the Australian Navy during its Orwellian slogan-named "Operation Sovereign Borders", the Chinese incursions into Indonesia's Exclusive Economic Zone and Territorial Sea will do more than poke Indonesia's hot-button regarding its territorial integrity. It will produce an ongoing policy dilemma for Indonesia. Australia claimed that during its six incursions its Navy had at all times intended maintaining navigation outside Indonesian territory, and had entered Indonesian territory only through inadvertence."Each incursion was inadvertent and occurred as a result of miscalculation of Indonesian maritime boundaries by Australian crews." according to an official Navy review. Whatever difficulties anyone might have in believing Australia's position, while there was certainly an infraction of Indonesian sovereignty, there was no challenge to it. It was what Indonesian Defence Minister Ryamizard Ryacudu might term "just a disciplinary violation".

On the other hand, China's response to the Kway Fey incident is unapologetic. It remains a challenge to the stated territorial position of Indonesia.

Blowing Up Boats

Indonesian Fisheries Minister, Susi Pujiastuti, has made it a policy position to publicly destroy boats arrested for illegally fishing in Indonesian waters. Her position, although inflammatory, is domestically popular.

Susi however did not invent the idea. In the early 2000's Australia began burning the boats of Indonesian fishermen which it had arrested inside its exclusive economic zone. Historically these waters must have indisputably been fished by Indonesian fishermen traditionally - especially the seeking of trochas shells from the area of Ashmore reef - much closer to the Indonesian major settled islands than to the Australian mainland.

The practice of Indonesian traditional fishermen in Australian waters has been going on for centuries and has historic and cultural significance as well as economic association with islands and reefs in Australian waters, mainly for fresh water, fishing, and shelter as well as to visit grave sites.

The historical evidence points to the regular use of Ashmore Reef by Indonesian fishermen beginning sometime between 1725 and 1750.

With the establishment of commercial ties with China in the 17th century, an international trade in preserved marine products began; Indonesian artisanal fishermen were regularly visiting northern Australia to harvest trepang by the end of 17th century.

In 1952 Australia unilaterally claimed the living natural resources of the continental shelf and in 1968 obtained validation of that claim through UNCLOS.

Starting in the 1970s, the area around Ashmore, Cartier and Scott reefs was progressively - and unilaterally - claimed by Australia as part of the country's expansion of sovereignty to 200 nautical miles from the coast.

Trochas is a sedentary fishery and as such continuous occupation and acquiescence may create rights in sedentary fisheries outside the normal ambit of the territorial sea. Brownlie has observed that "Sedentary fisheries...are capable of possession: but it is probable that the rights obtained are less than sovereignty".

Australia initially recognized the Indonesian long tradition of fishing in the waters but restricted this to subsistence level carried out in the 12nm fishing zone and territorial sea adjacent to Ashmore and Cartier Islands, Seringapatam Reef, Scot Reef, Browse Island and Adele Island. As part of that process in 1974 Australia and Indonesia signed a memorandum of understanding concerning traditional fishing, and later a 1992 agreement relating to co-operation in Fisheries.

In 1979 Australia expanded its fishing zone from 12 nautical miles to 200 nautical miles at the expense of Indonesian traditional fisheries on what had previously been the high seas.

The more recent events which have determined if not altered the position between Australia and Indonesia are those two countries' entry into UNCLOS and later a bilateral treaty delimiting maritime borders by agreement. Australia has taken the position that Indonesian traditional fishing rights are now extinguished.

Australia's continental shelf claim extended underneath Indonesia's exclusive Economic Zone claim with the result that in the overlap, Australia has rights to sedentary species and Indonesia has rights to the pelagic species - made complex by the inability of Australia to enforce its sovereign rights in the seabed without access to the Indonesian water column.

Indonesia recognises the concept of "Traditional Fishing Rights"

Traditional fishing rights were once universally accepted by the international community and explicitly recognized by domestic legislation, bilateral fisheries agreements, multilateral fisheries conventions, delimitation agreements and the International Court of Justice which upheld a claim of German traditional fishing rights against Iceland's unilateral declaration of an extended Exclusive Economic Zone. The nature of such rights at customary international law overshadows Australia's attempts to equate "traditional" with "subsistence".

Indonesia has previously entered into express arrangements with Australia, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea with respect to traditional fishing rights.

Indonesia has also claimed Archipelagic status under UNCLOS - this gives rise not just to rights - but also to obligations. One of those obligations is to recognize the traditional fishing rights of other immediately adjacent states within its archipelagic waters. if UNCLOS requires that of archipelagic waters it would seem difficult to imply an intention in UNCLOS to exclude recognition of traditional fishing rights in the Exclusive Economic Zone outside the archipelagic waters.

The express requirement for archipelagic states to obtain sovereignty in otherwise sovereign waters subject to claims to access for traditional fishing rights, might found a legal argument that there was no intention that UNCLOS remove customary international law rights to traditional fishing in waters outside sovereign territory.

Indonesia recognizes Malaysian traditional fishing rights in Indonesian archipelagic waters.

Indonesia is obliged by article 62 of UNCLOS to "promote the optimum ultilisation of the living resources in the [EE] zone" including determining its own harvest capacity and giving access to harvest above its own capacity and up to the sustainable limit to other states. In giving access to other states it must take into account "all relevant factors".

The concept of "traditional fishing waters" would be a relevant factor in granting preference to China in an allocation within Indonesia's exclusive economic zone. So China may raise the issue as something approaching a right under UNCLOS, especially if Indonesia is not properly fulfilling its management of the EEZ in accordance with UNCLOS.

Indonesia's management of fisheries resources is improving rapidly under Susi Pujiastuti, but if it's currently on par with its management and allocation of oil resources or many of its other public service functions, I suspect that China's arguments will get some degree of purchase.

The limits of UNCLOS

The preamble to UNCLOS includes the following:

'Desiring by this Convention to develop the principles embodied in resolution 2749 (XXV) of 17 December 1970 in which the General Assembly of the United Nations solemnly declared inter alia that the area of the seabed and ocean floor and the subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction, as well as its resources, are the common heritage of mankind, the exploration and exploitation of which shall be carried out for the benefit of mankind as a whole, irrespective of the geographical location of States

Affirming that matters not regulated by this Convention continue to be governed by the rules and principles of general international law'

So how far can UNCLOS go in regulating the seabed, ocean floor and therefore sedentary fisheries and bottom trawling outside the 1970 national jurisdiction? In the case of Indonesia that means the traditional territorial sea.

How far does UNCLOS replace or over-ride the general international law concept of traditional fishing rights?

A lawyer might say, "It's an argument."

The Nine Dash Line

The obligations of UNCLOS of archipelagic states to accommodate traditional fishing rights within otherwise sovereign archipelagic waters are in favour of immediately adjacent states.

China's nine dash line overlaps the section of Indonesia's 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone in an area north east of Natuna islands where the incident occurred. If China is an "immediately adjacent" state, it will have traditional fishing rights in terms of UNCLOS.

Furthermore the incident is likely a deliberate litmus test from a nation whose premier when asked in 1972 his view on the French Revolution responded that it was, "too early to tell". Likewise with the outcome of this international law incident, which illustrates that like many situations where disputants look to the law and even when a rules based order approach is taken, a diplomatic resolution might be attractive.

Add Pingback